[datacenter_tag_image]

This five-part series explores the operational characteristics of diesel fuel, which is the most common form of industrial-scale backup generation. With the rapid rise of AI-driven data centers, the series will examine how conventional backup practices need to adapt to meet the industry’s growing demand for resiliency and performance.

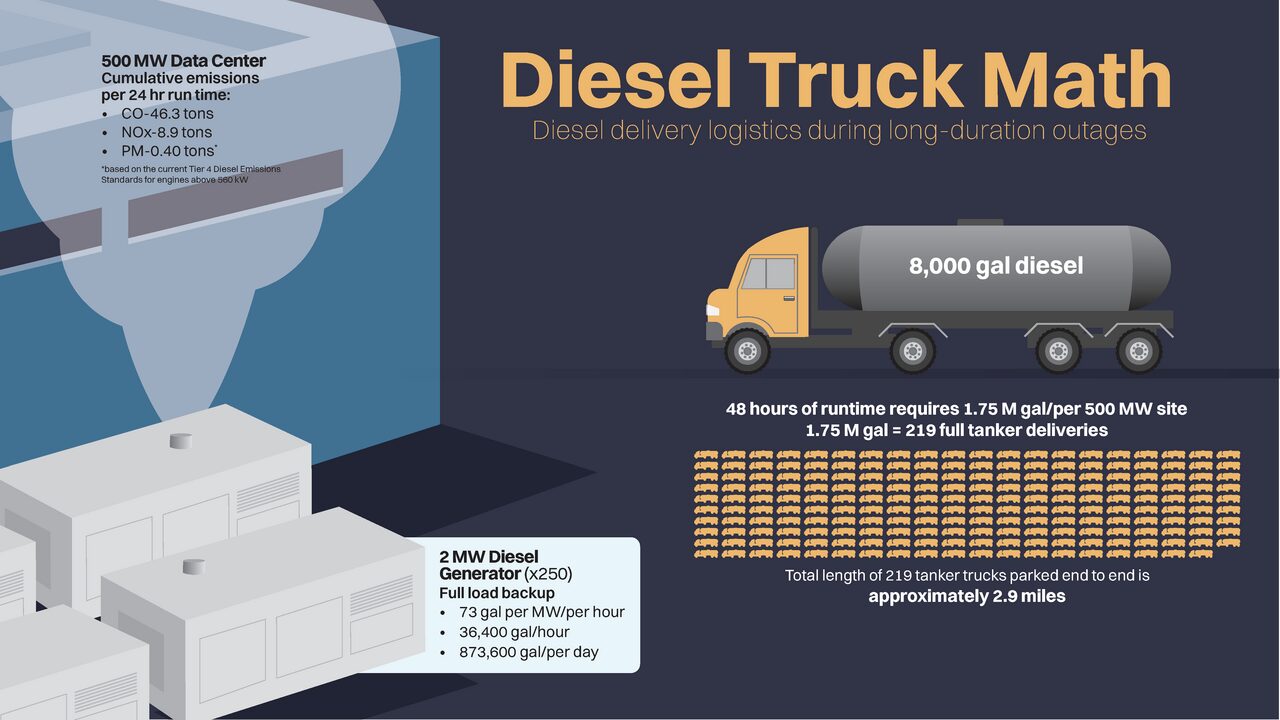

The second installment covers the “truck math” concept and why refueling for a 500 MW data center during an outage is nearly impossible.

In our last article, we looked at what it takes to power a 500 MW data center for 48 hours during extended outages caused by extreme weather. But the obstacles and delays related to fuel deliveries after a major storm are only half the story. The real challenge comes with getting enough diesel on site fast enough to keep the power on, even when the roads are clear. Let’s dig into the delivery side of the equation, what it would take to pull it off, and whether it’s even realistic at this scale.

At first glance, diesel backup seems simple: keep enough fuel onsite, and when it runs low, bring in more trucks. For small facilities, that might work, but at the scale of a 500 MW data center, the math turns into a logistical nightmare.

Large stationary diesel generators burn about 73 gallons per MW per hour at full load. Multiply that by 500 MW, and you’re looking at roughly 36,400 gallons an hour. That’s 873,600 gallons every day, nearly a million gallons gone in just 24 hours.

As noted in the previous article, most facilities store enough diesel for about 48 hours of runtime. That’s about 1.75 million gallons for a 500 MW site. And when the tanks run low, you need to refill them fast.

Here’s the catch:

Now picture the real-world constraints:

And all of this assumes perfect conditions. In reality, a major outage at a 500 MW data center facility is likely happening in the middle of extreme weather like icy roads, flooding, debris, or restricted access zones slowing everything down. Even a small hiccup—a delayed truck, a spill, or a route closure—can start a domino effect that puts uptime at risk. During Winter Storm Uri, for example, delayed diesel deliveries set off a chain reaction where hospitals, utilities, and data centers all competed for the same scarce fuel resources. Each missed delivery compounded the strain on the next facility in line, turning localized shortages into a systemwide crisis.

From a number’s perspective, diesel backup doesn’t scale. A 500 MW site would require over 200 trucks every two days, each one subject to traffic, weather, or driver availability. The probability of flawless execution drops fast. By contrast, according to the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America, natural gas pipelines have historically delivered ~99.8% of firm contractual volumes to primary delivery points. In statistical terms, continuous pipeline supply is a much more reliable than betting on a convoy of trucks. And history has shown us that’s a bet you rarely win.

Next up: The supply chain crunch and why local fuel hubs can’t keep up with clustered demand.

This article was originally published on LinkedIn.